My 2015 Africa Reading Challenge

A website called Kinna

Reads initiated an Africa Reading Challenge

with a simple rule: read at least 5 African books in the period of January 1,

2015 and December 31, 2015. I thought this was a great excuse to venture into a

large range of quality African books which the world is finally starting to

notice. It also fit in very conveniently with the personal challenge I had

already given myself a few years ago to read more African books. The goal of my

challenge was to begin to familiarise myself with African writing, since my

intention is to be published amongst that group. I grew up preferring western

novels for reasons I have discovered have more to do with the global industry

(availability, advertising, what type of African books get published) than

actual quality.

Without

venturing into what can and cannot be defined as an African book, I made my

choice based on accessibility (to me) and interest. I sourced

them from a variety of places, secondhand book stores in South Africa, a South

African shopping website, a flea market in Zimbabwe, a bookstore in Malawi, my

mother's garage, and book swaps with my fellow writer friends.

The sad

thing about this list is that recommending these books only takes them so far.

There are still big problems with availability, especially in countries which

do not yet have an online payment system - most likely to be African countries!

There is no single source of African books, but they are around for those who

wish to find them.

Here are

my reviews in the order I read them - they are just my opinions, I encourage

you to read the books and decide for yourself.

Purple Hibiscus (Nigeria)

In the past, one of my excuses for avoiding African books is that they

tended to be depressing at their core. One bad thing after another happens to a

more or less passive protagonist, and they tended to not overcome their difficulties at all. I'm afraid

Purple Hibiscus fit that mold. The story follows a young Nigerian girl who

grows up as one of two siblings in a home with a strictly religious father who

abuses her mother. External political circumstances result in the girl and her

brother being sent to live in a poorer household with her father's sister and

their grandfather - who their father considers to be a "heathen" as

he still practices African religion. The girl has to reconcile adolescence, her

differences with other children whose parents raise them differently, and a

forbidden crush on a young pastor.

The

story was not hugely about character arch (although there was

some character growth), but more an analysis of morality, society dynamics

in Nigeria, poverty and wealth, and a few other themes, all seen through the

lens of a girl who, for the most part, did not have the power to change them.

It is more reality-based than the fantasy books I usually hunt for like a

bloodhound, so I'm aware that my assessment of it is biased. My favourite

fantastical idea that the young protagonist can change the world was

conspicuously absent for me. It was nonetheless an interesting read, which

I recommend to anyone whose taste leans more towards books that hold a mirror

up to the status quo, showing the good, bad and ugly alike.

A comment about the cover - although I'm here to review the

story, the chosen cover was very distracting. From the research I have done in

the publishing industry I know that the author rarely has control over the

cover, so I fault the publishers. The girl on the cover is shown to be of

light, possibly Caucasian skin tone, but there is no girl of

that ethnicity in the entire book. The main character's racial

descriptions are very clear, down to vivid descriptions of her natural African hair

- this is not an ambiguous black Hermione situation. The reason I'm so emotional about this is

that I wonder why they were trying to mislead readers. Was there a presumption

that fewer people would buy a book with a black female on the cover? That sends

chills...

Half of a Yellow Sun (Nigeria)

This

book used the "mystery title" hook for me - I drove forward with the

question in the back of my mind - what does Half of a Yellow Sun mean? I won't

spoil it here, but will assure you that it does answer the question.

It was

another book which deals with depressing topics (although admittedly not to the

extent Hibiscus does) with the

second half immersed in war, and some quite vivid violent

imagery which stayed with my imagination long after I put the book down. While

I would much rather absorb happier things like I have mentioned, the book

taught me a great deal about a war which I had no idea happened (due to the

near absence of African history in my entire primary and secondary school

curriculum). I even had to do further research to find out to my surprise that

it wasn't fictional.

In this

book Adichie dealt with relationship dynamics better than Purple Hibiscus, addressing how an

intercultural/interracial relationship copes, how infidelity impacts a

relationship, how a drastic change in lifestyle from having plenty to having

nothing impacts different relationships, and other fascinating scenarios.

One of

the protagonists has a non-identical twin sister like me, which I haven't seen

explored much - writers are usually more fascinated with the "what if I

could swap places with an identical twin" trope. Instead Adichie wrote

their relationship quite pragmatically, as they realistically have different

personalities and tastes. The author's pragmatism extended to all the

characters' relationships, writing them in a way that made them feel like fully

fleshed people.

The

publishers finally created a cover representing the true ethnicity of the

character, but I noticed for the next Adichie book Americanah they pretty much

redid the cover, as if it was a continuation of a series instead of an

independent book. The version I read was published in Kenya so you won't see

that twin cover of Half of a Yellow Sun here (Google was invented for this

precise purpose however).

Americanah (Nigeria)

At last

my perseverance with Adichie's books paid off. This book is not just

my favourite of her books, it isn't just my favourite African book, it's

one of my favourite books ever. It made me realise how important representation

truly is. For the first time, I encountered a character who, like me; was an

educated black African female; who grew up believing her hair was out of place;

and lived in a foreign country which firmly differentiated her own blackness

with the local blackness (breaking initial assumption that the black experience

is the same everywhere - it's not).

The

story begins with an introduction to Ifemelu, a young Nigerian woman studying

in America at Princeton, but has to leave town just to get her hair braided

because there are no black hairdressers in the predominantly white town. The

salon is used as a base scene, from which the various aspects of Ifemelu's life

are explored through flashbacks; her observations about

race, nationality and immigrant life in the African diaspora, the

life changing decision she has made about moving from America back to

Nigeria, and her love life in all of its complexity. Her frank observations

about the world around her are eye-opening and immediately relatable, so that

the story feels realistic enough to seem like a documentary on the human

experience through a black female perspective.

One of

the things I love about this story is that it actually shows black love instead

of domestic abuse or some other messed up situation. There are challenges in

the relationships portrayed, but not because one of them is a Scary Black Man

or a Conniving Black Woman, which are too often the go-to characters in African

relationship plot lines. Instead through her story, Adichie explored the impact

of distance, miscommunication, cultural traditions, and careers on

relationships.

Rumours have said there will be a movie based on this story and I just can't wait.

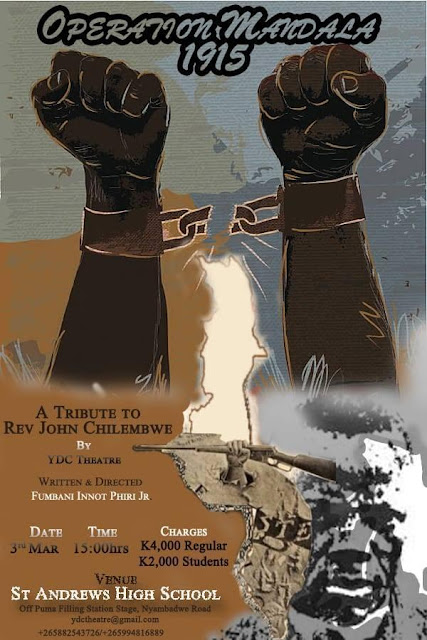

Smouldering Charcoal (Malawi)

I was

lucky enough not to have studied that book in secondary school like my fellow

writers. That means I picked it up by choice, when I was arguably at the right

age, maturity and level of political consciousness to appreciate and understand

it. I think it might have bored me if I had read it as a teenager, unable to

appreciate what it meant for my direct history.

The book

is set in post-colonial, pre-democratic Malawi. The viewpoint takes two

perspectives, that of a poor character, and that of a well-to-do character.

They have two different experiences of the regime, but what they have in common

is a sense of restricted freedom, and the ever present possibility of their

lives being forcibly changed for the worse in a single moment.

When I finished reading it, I suddenly realised how brave this book

had to be, because it was published when Kamuzu Banda was still in power. It was loosely coded, with no mention of what

country it is based in, nor the name of the Leader or his political Party.

However, anyone with any knowledge of Malawian history will know "The

Leader" is Kamuzu Banda, and "The Party" is the Malawi Congress

Party. The coding was not a marketing gimmick like

I initially thought, it was the author's survival technique. I am not

even certain if the author used their own name or a pseudonym, because I

heard of many Malawian citizens who had to change their names in order to

escape harsh prosecution for opposing the one party government.

Smouldering

Charcoal was history in the form which I prefer to consume it - through the

eyes of characters in a story. I was born in the last few years of Kamuzu's

life, so was never really aware of the oppressiveness, but I got to learn about

what life was really like in my parent's time. It was too recent for my history

teachers to cover.

Africa 39 (Pan-African)

This

concept behind this anthology is not theme, but rather a collection of 39 of

Africa's emerging writers from Sub-Saharan Africa. Among the themes which the

authors are free to explore, there are stories about the key historical figures

on both the African and European side of colonialism; a friendship between two

different people who have heartbreak in common; a futuristic society where some

of the population is kept in the dark about what is really happening; the

dilemmas of a white Nigerian who does not fit into either of the two worlds he

is from; and a metaphorical piece about Mama Africa who is dying and how her

children (who represent various groups of people of African heritage) respond

to this sombre news. The stories explore many different avenues, the future,

the past, the present, and the mind itself.

The Granta Book of the African Short Story (Pan-African)

This

anthology is grounded primarily in realism, with stories depicting segments of

lives lived around the continent. The exception was a story named Faeries of

the Nile, which dealt more with an abused woman's response to mystical

creatures which she is unsure even exist.

At times

the stories are violent, brutal, depressing and often shows the

ugliest sides of life and humanity. Honestly, there was too little hope in

these stories for me to enjoy them very much. I am glad I read the book because

I learnt about different places and cultures as well as different styles of

writing, but ultimately it was not my cup of tea. A story which I did like, although it took the same tone of staring into the face of society's ugliness, was "Preference Nationale". It portrayed a francophone African's difficulty earning a decent life in France. The irony struck a cord - an African coming to the country which had historically colonised her own, changing her identity down to the language, yet was rejected by embedded xenophobia and racism.

Omenana (Pan-African)

Those

with keen eyes may notice that my name is in there... I will try and be as

unbiased as possible! These series of anthologies are produced in Nigeria, but

Pan-African in content. They are beautifully illustrated collections of

speculative fiction stories - in other words science-fiction, fantasy, magical

realism, horror, any genre which explores that which is beyond what we perceive

as possible. Many stories build on the existing superstitions and

mystical beliefs within the hugely diverse African mythos, and blend them into

the modern world. This juxtaposition between the familiar and strange make for

some memorable tales which capture the imagination.

There

are stories of a massage client with disturbing but seductive abilities; a jinn

man who is distanced from the love of his life because of his body's tendency

to burn boiling hot; an epic short story which traces a mixed race bloodline

from the past to the present to the future; and an 18th century African slave

imprisoned in a French dungeon struggling to use his remaining energy and magic

to create an invention which is destined to change the world.

The best thing about the Omenana series is that they are

available right now, for free, downloadable here! They also

showcase visual art, both on their covers and as stand alone pieces next to the

stories. If you're an African spec-fic writer or an artist, I'd encourage you to take a look and submit your material to them.

Imagine Africa 500 (Pan-African)

This is a book I am still reading, and feel a little bad

about promoting it since it is not yet widely available! But for sure it is one

to look out for soon. This is a matter of pride because it is the first science

fiction anthology produced by a Malawian, including stories by five Malawian

writers I personally know. It is the direct product of the Imagine

Africa 500 workshop which I have blogged

about.

The

stories in the anthology dream up different versions of the future, some

dystopian, post-apocalyptic, others hopeful and fantastical. Some predict we

will go back to basics, rejecting the technology and economic systems of the

present day to embrace sorcery, swords and kingdoms. Others warn us that the

future may make us pure survivalists at the complete mercy of nature, having

ignored it for far too long. Others paint a future with many of the same

problems of economically unequal societies, of education only favouring the

wealthy, and large groups of people trapped in a hopeless future which is

reinforced by authority. The best thing about science fiction stories is that

they can show us on the vivid plane of the imagination, where we could end up,

and where we should avoid ending up. We need both the positive and negative

stories to guide us, and this anthology has a delicious blend of both.

(For an in depth review of one of the stories written by Malawian Muthi Nhlema, visit Joanna Wood's website Zwelethemba: 'Land of Hope')

End Note

It

doesn’t have to end in 2015 - you can challenge yourself next year! I certainly

have not finished my personal African book quest, especially now that sci-fi and fantasy are becoming easier to find.

After African books, I want to read books by other non-western

writers, like Asian, South American, middle eastern and so on. I have become

more open-minded about where great stories can come from - they are not always

the ones which shout the loudest. Let me know if you hear of a great book from an unusual source!

Honourable Mention:

Zoo City (South Africa), which I read in 2014 and already reviewed here.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Dishonourable Mention!

Perhaps

there was a time when I had enough willful ignorance to finish a book like

this, but I actually had to put this one down. It is clearly Africa through the

white male gaze, an unapologetic macho adventure through deepest

"darkest" Africa, conquering it one adrenelin gun fight at a time. I

hated how a third of the way through, there was still no significant African

character with their own motivations that weren't sneaky or bloodthirsty. I

skipped through and found that the only black female was described as "the

biggest ugliest woman Dirk had ever seen" (paraphrasing). I put it down

when I reached a scene where 3 westerners were gleefully gunning down a crew of

Africans - all justified of course, they attacked first, and they clearly had

evil intentions. But the fact that the Africans were split between "those

you gun down" and "those you rescue from their African-ness"

totally repulsed me. Those have watched the movie adaptation may notice that

the racism and sexism has been vastly played down for a diverse movie audience. As a matter of fact I personally enjoyed the film before I had the displeasure of reading the source material.

Of

course it is not Cussler's responsibility to represent a variety of dimensions

of Africa which reflect a dignified Africa. He is good at appealing to the audience

he aims for. It is our duty as African writers to tell better stories about

ourselves.

Comments

Post a Comment